One day in late 2013, Keith Spiller went for a walk around a city in the south of England. Over the course of about an hour and a half, he walked past the town hall, a train station, a stadium, a few banks, a few shopping areas, a museum and a handful of other public places. And, like countless others walking around UK cities and cities around the world, in each of the places he passed he was recorded on CCTV surveillance cameras.

After his walk, however, he did what very few others do: he asked for the footage.

The UK’s Data Protection Act of 1998 entitles the public to access this kind of personal data, and Spiller, a researcher at the Open University in Milton Keynes, wanted to see how well CCTV operators complied with the law. He found the contact information for the operators of the cameras in each of the 17 locations he visited, and began submitting subject access requests to see what the cameras had recorded. He recently published his research in the journal Urban Studies.

“What I asked them to do is relatively unusual,” Spiller says. “[With] most members of the public, the chance of them asking for their images is limited. I think on average most people only look for it when something has happened to them or something’s gone wrong. And even then, I’m not so sure people are aware they have a right to look at their own information.”

They do have the right, technically. But in practice, actually getting the footage is not as straightforward as the law might make it seem.

Sometimes the responses given were just to kind of hope I would go away

Keith Spiller Facebook Twitter Pinterest CCTV cameras on the side of a building in central London. Photograph: Clive Gee/PA

Following the protocol laid out in the Data Protection Act, Spiller made formal written requests to the operators of each of the 17 CCTV cameras that recorded him, using a template letter from the UK Information Commissioners’ Office. According to the ICO, 94,358 organisations across the UK have registered as users of CCTV. Operators are compelled to provide requested data within 40 days, and are allowed to ask a £10 fee from the requester. In some cases, Spiller received quick mailed responses seeking the £10 fee – and one requesting a £20 fee, plus VAT. In others, his requests went unanswered.

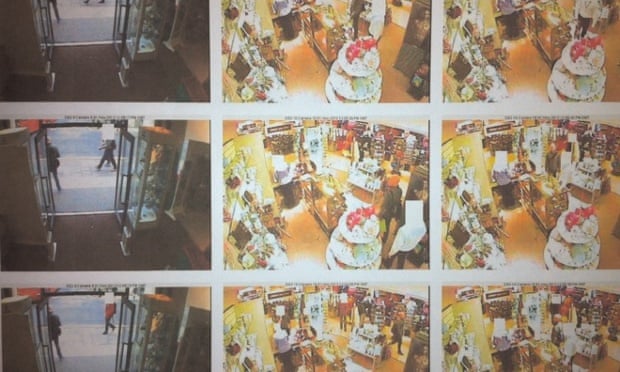

He then made follow-up calls, some of which went unreturned while others revealed that his original letters were either lost or never received. In one back-and-forth with the operator of a shopping mall’s CCTV system, the correspondence lasted so long that by the time the operator figured out how to get Spiller what he requested, the system’s 30-day automatic data overwrite had already deleted his footage.

“The data controllers tasked with actually giving information back to the person who’s caught on CCTV, because they don’t do it that often, quite often aren’t too sure what they have to do,” he says. “Sometimes the responses that were given were just to kind of hope that I would go away.”

In total, Spiller wrote 37 letters, made 31 phone calls, and spent £60 making requests. Of the 17 CCTV operators he contacted, only six provided him with his footage.

He had about the same success rate as The Get Out Clause, a Manchester band that performed in front of the city’s surveillance cameras in 2008, requested the footage from about 80 cameras and used the roughly 20 clips they received to make a music video .

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Graffiti outside the Hubb Arts Centre in Sparkbrook, Birmingham. Photograph: David Sillitoe for the Guardian

For Spiller, his underwhelming results are indicative of a lack of oversight in the extensive CCTV surveillance system operating in private and public spaces across the UK. Though the rules are clearly outlined in the Data Protection Act, they’re not well observed, and Spiller worries that the organisations collecting this data aren’t being adequately scrutinised. “In this day and age, it’s an extremely pressing issue as to how our data is managed by third parties,” he says. “This is one of the big debates for the future.”

And it’s an issue of growing global concern, with new surveillance technologies being deployed on a large scale in cities around the world. Spiller’s research was conducted as part of a 10-university, EU-wide examination of surveillance that found widespread limitations on the public’s ability to access data collected by these systems, despite rules such as the UK Data Protection Act and the EU’s Data Protection Directive .

Related: Predicting crime, LAPD-style

In the United States, where citywide surveillance systems, police car-mounted automated license plate readers and body-worn cameras are being adopted across the country, many are concerned about the lack of regulations controlling how this data is being collected, stored and made available, especially when the collection is happening in public spaces.

“It’s always been true that people routinely engage in activities in public spaces that they nonetheless consider to be private. And not that long ago, the government encroaching on that expectation of privacy wasn’t really an issue, because it didn’t have the capability to do so. It does now,” says Scott Roehm, vice-president of programmes and policy at the Constitution Project, a Washington DC thinktank. “Technology, including what’s doable with a public video surveillance system, is rapidly de-anonymising public spaces, and the law hasn’t yet caught up.”

Unlike the UK and EU, the US doesn’t have nationwide policies governing surveillance systems and their accessibility – aside from general protections against unreasonable searches in the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution . Some cities with citywide CCTV and surveillance systems – such as New York, Washington DC and Chicago – do have some policies governing how these systems are used, but many others don’t.

At the state level, the default policy has been each state’s version of freedom of information or public records laws, says Nancy La Vigne, director of the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute, a research group focused on urban issues. How and whether footage can be disseminated varies from state to state. “That leads to some states being really forthcoming with the footage, and other states less so,” she says.

Technology is rapidly de-anonymising public spaces, and the law hasn’t yet caught up

Scott Roehm Facebook Twitter Pinterest A CCTV camera in front of a poster in central London. Photograph: Toby Melville/Reuters

The lack of clarity creates the potential for abuse, according to Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst at the American Civil Liberties Union. The pace at which cities and police departments are adopting new technologies, such as body-worn cameras and facial recognition technology, has tended to be much faster than the development of clear regulations to govern how these new technologies are used.

“We are seeing the creeping introduction of government-run cameras, and generally there aren’t really policies in place on most of them,” Stanley says. “There’s a lag between when people lose their privacy and when they feel like they’ve lost their privacy. We’re in that lag period now.”

Groups like the ACLU and the Constitution Project have called for more specific policies, and each has developed model legislation that municipalities can use to put more safeguards in place as they roll out these new technologies. Roehm of the Constitution Project says that developing regulations and standards at the outset is key to protecting the public’s constitutional rights and civil liberties once the cameras are rolling.

“There are ways to build a system that would make it more protective, allow for more transparency, solve some of the problems that exist now – but it requires doing all that work at the front end and then following through,” he says.

Related: The privatisation of cities' public spaces is escalating. It is time to take a stand

In the UK, the system is in place – but, as Spiller’s research shows, there’s room to improve on the follow-through. He argues that the reason CCTV operators can have such a poor record of complying with requests is that they aren’t held accountable as often as they should be.

If people want a more transparent system, he says, they should be making their own requests for CCTV footage.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion